The first step in developing a segmentation strategy is to select

the most appropriate base on which to segment the market. Nine major categories

of consumer characteristics provide the most popular bases for marketers market

segmentation. They include geographic factors, demographic factors,

psychological factors, psychographic (lifestyle) characteristics, sociocultural

variables, userelated characteristics, use-situation factors, benefits sought

and forms of hybrid segmentation such as demographic-psychographic profiles and

geodemographic factors.

Hybrid segmentation formats each use a combination of

several segmentation bases to create rich and comprehensive profiles of

particular consumer segments (e.g. a combination of a specific age range,

income range, lifestyle and profession). Table 1 lists the nine segmentation base,

divided into specific variables with examples of each. The following section

discusses each of the nine segmentation bases. (Various psychological and

sociocultural segmentation variables are examined in greater depth in later plengdut.com post.)

TABLE 1 Market segmentation categories and selected variables

SEGMENTATION BASE

|

SELECTED SEGMENTATION VARIABLES

|

GEOGRAPHIC SEGMENTATION

|

|

Region

|

Scandinavia, Benelux, Middle East

|

City size

|

Major metropolitan areas, small cities, towns

|

Density of area

|

Urban, suburban, exurban, rural

|

Climate

|

Temperate, hot, humid, rainy

|

DEMOGRAPHIC SEGMENTATION

|

|

Age

|

Under 12, 12–17, 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65–74, 75–99, 100+

|

Sex

|

Male, female

|

Marital status

|

Single, married, divorced, living together, widowed

|

Income

|

Under €25,000, €25,000–€34,999, €35,000–€49,999,

€50,000–€74,999, €75,000–€99,999, €100,000 and over

|

Education

|

Some high school, high school graduate, some university,

university graduate, postgraduate

|

Occupation

|

Professional, blue-collar, white-collar, agricultural,

military

|

PSYCHOLOGICAL SEGMENTATION

|

|

Needs-motivation

|

Shelter, safety, security, affection, sense of self-worth

|

Personality

|

Extroverts, novelty seekers, aggressives, low dogmatics

|

Perception

|

Low-risk, moderate-risk, high-risk

|

Learning-involvement

|

Low-involvement, high-involvement

|

Attitudes

|

Positive attitude, negative attitude

|

PSYCHOGRAPHIC SEGMENTATION

|

|

Combines psychology and demographics, hence psychodemographics

(Lifestyle) Segmentation

|

Economy-minded, couch potatoes, outdoors enthusiasts, status

seekers

|

VALS™

|

Innovator, Thinker, Believer, Achiever, Striver, Experiencer, Maker,

Survivor

|

SOCIOCULTURAL SEGMENTATION

|

|

Cultures

|

Danish, Italian, Chinese, Australian, French, Pakistani

|

Religion

|

Catholic, Protestant, Moslem, Jewish, other

|

Subcultures (race/ethnic)

|

African, American, Caucasian, Asian, Hispanic

|

Social class

|

Lower, middle, upper

|

Family life cycle

|

Bachelors, young marrieds, full nesters, empty nesters

|

USE-RELATED SEGMENTATION

|

|

Usage rate

|

Heavy users, medium users, light users, non-users

|

Awareness status

|

Unaware, aware, interested, enthusiastic

|

Brand loyalty

|

None, some, strong

|

USAGE-SITUATION SEGMENTATION

|

|

Time

|

Leisure, work, rush, morning, night

|

Objective

|

Personal, gift, snack, fun, achievement

|

Location

|

Home, work, friend’s home, in-store

|

Person

|

Self, family members, friends, boss, peer

|

BENEFIT SEGMENTATION

|

|

Convenience, social acceptance, long lasting, economy, value-for-money

|

|

HYBRID SEGMENTATION

|

|

Geodemographics

|

‘New empty nests’, ‘Boomtown singles’, ‘Movers and Shakers’

|

Note: VALS™ is an example of a psychographic/demographic

profile.

Source : Reprinted with permission of Strategic Business

Insights (SBI); www.strategicbusinessinsights.com/VALS .

Geographic segmentation

In geographic segmentation the market is divided by

location. The theory behind this strategy is that people who live in the same

area share some similar needs and wants and that these needs and wants differ

from those of people living in other areas. For example, certain food products

and/or varieties sell better in one region than in others, or are used

differently in different geographic areas. More specifically, mayonnaise is

frequently used with chips in Belgium, whereas this combination is seldom seen

in Norway. Furthermore, while curry-fl avoured ketchup has been a well-known

product in Belgium for years, the same product has until recently been

difficult to find in Norwegian supermarkets.

Some marketing scholars have argued that direct-mail

merchandise catalogues, national tollfree telephone numbers, satellite

television transmission, global communication networks, and especially the

Internet have erased all regional boundaries and that geographic segmentation

should be replaced by a single global marketing strategy. Clearly, any company

that decides to put its catalogue on the Internet enables individuals all over

the world to browse its site and become customers. For example, shops offering

collectables like first editions of old books may increase their target segment

substantially by making their inventory searchable on the Internet.

A shop in Greece may find that orders start coming in from

Sweden, Japan, New Zealand and Ireland not long after posting its offer on the

Internet. Other marketers have, for a number of reasons, been moving in the

opposite direction and developing highly regionalised marketing strategies. For

example, due to the variety of consumer preferences, government regulations and

brand images, General Motors segments the European market into a multitude of

regions. Within each region, GM sales managers have the authority to develop

specific advertising and promotional campaigns geared to local market needs and

conditions, using local media ranging from newspapers to television

commercials. In addition, the product specifications are adapted to the

different local markets. For example, the Astra model is offered under the

Vauxhall brand in the UK and comes with the steering wheel on the right-hand

side of the car. In contrast, the same model is marketed under the Opel brand

in Germany, and in compliance with the needs of German drivers the steering

wheel is on the left. If we look beyond Europe, the Astra model is offered

under a third GM brand in Australia, where it is called Holden Astra. Again,

the steering wheel is on the right-hand side.

Marketers have observed divergent consumer purchasing

patterns among urban, suburban and rural areas. For example, while Norwegians

have often associated cognac consumption with urban lifestyles or upscale

restaurants, sales reports indicate that consumers in more rural areas consume

more of this product than people living in more densely populated areas like

the capital city of Oslo. In fact, the average inhabitant of Finnmark, the most

northern and least populated part of Norway, consumes a total of 0.8 litres a

year, while the average Norwegian consumes only 0.3 litres annually. In

contrast, the average Swede consumes only 0.06 litres a year. Such

geographically different consumption patterns have implications for the

producers and distributors of the product in question.

In summary, geographic segmentation is a useful strategy for

many marketers. It is relatively easy to find geographically based differences

for many products. In addition, geographic segments can be easily reached

through the local media, including newspapers, television and radio, and

regional editions of magazines.

Demographic segmentation

Demographic characteristics , such as age, sex, marital

status, income, occupation and education, are most often used as the basis for

market segmentation. Demography refers to the vital and measurable statistics

of a population. Demographics help to locate a target market, whereas

psychological and sociocultural characteristics help to describe how its

members think and how they feel. Demographic information is often the most

accessible and cost-effective way to identify a target market.

Indeed, most secondary data, including census data, are

expressed in demographic terms. Demographics are easier to measure than other

segmentation variables; they are invariably included in psychographic and

sociocultural studies because they add meaning to the findings. Demographic

variables reveal ongoing trends that signal business opportunities, such as shifts

in age, gender and income distribution. For example, demographic studies

consistently show that the ‘mature-adult market’ (the 50+ segment) has a much

higher proportion of disposable income than its younger counterparts. This

factor alone makes consumers over the age of 50 a critical market segment for

products and services that they buy for themselves, for their adult children

and for their grandchildren. In fact, some marketing scholars have termed the 50+

segment ‘Power consumers’, based on the high purchasing power this segment

possesses.

Age segmentation

Product needs and interests often vary with consumers’ age.

For instance, investors younger than 55 have been found to base their

investment decisions on long-term gain and consider current income and intermediate

gain less important, whereas investors over 55 tend to be more cautious and

place more importance on the intermediate gain and current income of a

potential investment.1 Because of such age motivated differences, marketers have

found age to be a particularly useful demographic variable for market

segmentation. Many marketers have carved themselves a niche in the marketplace

by concentrating on a specific age segment. For example, although children

often consume boxed juice drinks, Minute Maid Company ( www.minutemaid.com ) offers

single-serve drinks in pouches, rather than boxes, in order better to appeal to

the ‘tween’ market. And one of the reasons why Heinz introduced EZ Squirt

ketchup (which included one version green in colour) was the better to appeal

to tweens. Still further, in seeking to cater to consumers under 25 years of

age, Pepsi (www.pepsi.com) understood that the Internet represented the primary

medium of choice and, therefore, increased its effort to create online

programmes directed at this audience.

TABLE 2 Segmentation by seven life development stages

MAJOR PHASE NAME

|

AGE

|

LIFE DEVELOPMENT STAGE (AGE)

|

MAJOR STAGE TASK

|

Provisional Adulthood

|

18–29

|

Pulling Up Roots

|

Detaching from family, searching for identity, choosing a

career

|

First Adulthood

|

30–49

|

Reaching Out (30–35)

|

Selecting a mate, working on career

|

Questions/Questions (36–44)

|

Searching for personal values, re-evaluating relationships

|

||

Midlife Explosion (45–49)

|

Searching for meaning, reassessing marriage, relating to teenage children,

with depression

being common in this stage

|

||

Second Adulthood

|

50–85+

|

Settling Down (50–55)

|

Adjusting to realities of work, adjusting to an

empty nest, being active in community

|

Mellowing (56–64)

|

Adjusting to health problems, approaching retirement

|

||

Retirement (65+)

|

Adjusting to retirement, reassessing finances, being concerned

with health

|

Source : Adapted from Linda Morton, ‘Segmenting Publics by Life

Development Stages’, Public Relations Quarterly , Spring 1999, 46; as based on

Gail Sheehy, New Passages: Mapping Your Life Across Time (New York: Ballantine

Books, 1995).

Age, especially chronological age, implies a number of

underlying forces. In particular, demographers have drawn an important

distinction between age effects (occurrences due to chronological age) and

cohort effects (occurrences due to growing up during a specific time period).

Examples of the age effect are the heightened interest in leisure travel that

often occurs for people (single and married) during middle age (particularly in

their late fifties or early sixties) and the interest in learning to play golf.

Although people of all ages learn to play golf, it is particularly prevalent

among people in their fifties. These two trends are examples of age effects

because they especially seem to happen as people reach a particular age

category.5 Table 2 presents a series of life development stages related to

age effects.

In contrast, the nature of cohort effects is captured by the

idea that people hold on to the interests they grew up to appreciate. If 10

years from today it is determined that many rock and roll fans are over 60, it

would not be because older people have suddenly altered their musical tastes

but because the baby boomers who grew up with rock and roll have become older.

It is important for marketers to be aware of the distinction

between age effects and cohort effects: one stresses the impact of ageing,

whereas the second stresses the infl uence of the period when a person is born

and shared experiences with others of the same age. Table 3 presents a sample

of ‘defining moments’ that shaped particular age cohorts in specific countries

or regions. If we try to expand the list presented in Table 3 , events like

September 11, 2001, the tsunami in 2004, the financial crisis in 2008, Michael

Jackson’s death in 2009 and the Haiti earthquake in 2010, may all be more

recent examples of such defining moments for those who were affected. We must

remember that cohort effects are ongoing and lifelong.

TABLE 3 Examples of country-specific or region-specific cohort-defining moments

EVENT*

|

DATE

|

COUNTRY AFFECTED

|

John Profumo scandal

|

1963

|

UK

|

Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment and release

|

1964 and 1990

|

South Africa

|

Cultural Revolution

|

1966–1976

|

China

|

Six Days War

|

1967

|

Jordan, Israel and Egypt

|

Khmer Rouge Rule

|

1975–1979

|

Cambodia and South East Asia

|

Assassination of Anwar Sadat

|

1981

|

Egypt

|

Falklands War

|

1982

|

UK and Argentina

|

Assassination of Olof Palme

|

1986

|

Sweden

|

Tiananmen Square massacre

|

1989

|

China

|

Manuel Noriega’s arrest and extradition to USA

|

1989

|

Panama

|

Japanese Economic ‘bubble’ bursts

|

1991

|

Japan

|

Irish legalisation of divorce

|

1995

|

Ireland

|

*These events are not ranked in order of importance, but by

date. Source : Adapted from Charles D. Schewe and Geoffrey Meredith,

‘Segmenting Global Market by Generational Cohorts: Determining Motivations by

Age’, Journal of Consumer Behavior , 4, October 2004, 56. Copyright 2004.

Copyright John Wiley & Sons Limited. Reproduced with permission.

Sex segmentation

Gender is quite frequently a distinguishing segmentation

variable. Women have traditionally been the main users of such products as hair

colouring and cosmetics, and men have been the main users of tools and shaving

preparations. However, sex roles have blurred, and gender is no longer an

accurate way to distinguish consumers in some product categories. For example,

women are buying household repair tools and men have become significant users

of skin care and hair products.

It is becoming increasingly common to see magazine

advertisements and television commercials that depict men and women in roles

traditionally occupied by the opposite sex. For example, many advertisements

refl ect the expanded child-nurturing roles of young fathers in today’s

society. Much of the change in sex roles has occurred because of the continued

impact of dualincome households. One consequence for marketers is that women

are not so readily accessible through traditional media as they once were.

Because working women do not have much time to watch television or listen to

the radio, many advertisers now emphasise magazines in their media schedules,

especially those specifically aimed at working women.

Direct marketers have

also been targeting time-pressured working women who use mail-order catalogues,

convenient toll free numbers and Internet sites as ways of shopping for

personal clothing and accessories, as well as many household and family needs.

Recent research has shown that men and women differ in terms of the way they

look at their Internet usage. Specifically, men tend to click on a website

because they are ‘information hungry’, whereas women click on because ‘they

expect communications media to entertain and educate’.

Marital Status

Traditionally, the family has been the focus of most

marketing efforts, and for many products and services the household continues

to be the relevant consuming unit. Marketers are interested in the number and

kinds of households that buy and/or own certain products. Marketers also are

interested in determining the demographic and media profiles of household

decision makers (those involved in the actual selection of the product) to

develop appropriate marketing strategies.

Marketers have discovered the benefits of targeting specific

marital status groupings, such as singles, divorced individuals, single parents

and dual-income married couples. For instance, singles, especially one-person

households with incomes greater than €50,000, comprise a market segment that

tends to be above average in the use of products not traditionally associated

with supermarkets (e.g. cognac, books, loose tea) and below average in their

consumption of traditional supermarket products (e.g. ketchup, peanut butter,

mayonnaise). Such insights can be particularly useful to a supermarket manager

operating in a neighbourhood of one-person households when deciding on the

merchandise mix for the store. Some marketers target one person households with

single serving prepared foods and others with mini appliances such as small

microwave ovens and two cup coffee makers.

Income, Education and Occupation

Income has long been an important variable for

distinguishing between market segments. Marketers commonly segment market on

the basis of income because they feel that it is a strong indicator of the

ability (or inability) to pay for a product or a specific model of the product.

For instance, initially marketers of home computers under €1,000 felt that such

products would be particularly attractive to homes with modest family incomes.

However, low-priced PCs also proved to be quite popular with higher-income

families who wanted additional computers for younger family members.

Income is often combined with other demographic variables to

define target market more accurately. To illustrate, high income has been

combined with age to identify the important affl uent elderly segment. It also

has been combined with both age and occupational status to produce the so

called yuppie segment, a sought after sub-group of the baby boomer market.

Education, occupation and income tend to be closely

correlated in almost a cause-andeffect relationship. High-level occupations

that produce high incomes usually require advanced educational training.

Individuals with little education rarely qualify for high-level jobs. Insights

on Internet usage preferences tend to support the close relationship among

income, occupation and education. Research reveals that consumers with lower

incomes, lower education and blue-collar occupations tend to spend more time

online at home than those with higher incomes, higher education and white collar

occupations. One possible reason for this difference is that those in

blue-collar jobs often do not have access to the Internet during the course of

the working day.

Psychological segmentation

Psychological characteristics refer to the inner or

intrinsic qualities of the individual consumer. Consumer segmentation

strategies are often based on specific psychological variables. For instance,

consumers may be segmented in terms of their motivations, personality,

perceptions, learning and attitudes. ( Part 2 examines in detail the wide range

of psychological variables that inf uence consumer decision-making and

consumption behaviour.)

Psychographic segmentation

Marketing practitioners have heartily embraced psychographic

research, which is closely aligned with psychological research, especially

personality and attitude measurement. This form of applied consumer research

(commonly referred to as lifestyle analysis) has proved to be a valuable

marketing tool that helps identify promising consumer segments likely to be

responsive to specific marketing messages.

The psychographic profile of a consumer segment can be

thought of as a composite of consumers’ measured activities, interests and

opinions (AIOs) . As an approach to constructing consumer psychographic profiles,

AIO research seeks consumers’ responses to a large number of statements that

measure activities (how the consumer or family spends time, e.g. golfing,

gardening), interests (the consumer’s or family’s preferences and priorities,

e.g. home, fashion, food) and opinions (how the consumer feels about a wide

variety of events and political issues, social issues, the state of the

economy, ecology). In their most common form, AIO-psychographic studies use a

battery of statements (a psychographic inventory ) designed to identify

relevant aspects of a consumer’s personality, buying motives, interests,

attitudes, beliefs and values. Table 4 presents a portion of a psychographic

inventory designed to gauge ‘techno-road-warriors’, business people who spend a

high percentage of their working week travelling, equipped with laptop

computers, mobile phones with broadband network connection and electronic

organisers. Table 5 presents a hypothetical psychographic profile of a

techno-road-warrior. The appeal of psychographic research lies in the

frequently vivid and practical profiles of consumer segments that it can

produce.

TABLE 4 A portion of an AIO inventory used to identify

techno-road-warriors

Instructions: Please read each statement and place an ‘x’ in

the box that best indicates how strongly you ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’ with the

statement.

AGREE COMPLETELY

|

DISAGREE COMPLETELY

|

||||||

I feel that my life is moving faster and faster,

sometimes just too fast

|

[1]

|

[2]

|

[3]

|

[4]

|

[5]

|

[6]

|

[7]

|

If I could consider the ‘pluses’ and ‘minuses’,

technology has been good for me

|

[1]

|

[2]

|

[3]

|

[4]

|

[5]

|

[6]

|

[7]

|

I find that I have to pull myself away from email

|

[1]

|

[2]

|

[3]

|

[4]

|

[5]

|

[6]

|

[7]

|

Given my lifestyle, I have more of a shortage of time

than money

|

[1]

|

[2]

|

[3]

|

[4]

|

[5]

|

[6]

|

[7]

|

I like the benefits of the Internet, but I often don’t

have the time to take advantage of them

|

[1]

|

[2]

|

[3]

|

[4]

|

[5]

|

[6]

|

[7]

|

I am generally open to considering new practices and new

technology

|

[1]

|

[2]

|

[3]

|

[4]

|

[5]

|

[6]

|

[7]

|

TABLE 5 A hypothetical psychographic profile of the techno-road-warrior

• Goes on the Internet more than 20 times a week

|

• Sends and/or receives 50 or more email messages a week

|

• Regularly visits websites to gather information and/or

to comparison shop

|

• Often buys personal items via 800 numbers and/or over

the Internet

|

• May trade stocks and/or make travel reservations over

the Internet

|

• Earns €75,000 or more a year

|

• Belongs to several rewards programmes (e.g. frequent

flyer, hotel and hire-car programmes)

|

AIO research has even been employed to explore pet ownership

as a segmentation base. One study has found that people who do not have pets

are more conservative in nature, more brand loyal, and more likely to agree

with statements such as ‘I am very good at managing money’ and ‘It is important

for me to look well dressed’. Such findings can be used by marketers when

developing promotional messages for their products and services.

The results of psychographic segmentation efforts are

frequently refl ected in firms’ marketing messages. Psychographic segmentation

is further discussed later in the plengdut post, where we consider hybrid

segmentation strategies that combine psychographic and demographic variables to

create rich descriptive profiles of consumer segments.

Sociocultural segmentation

Sociological (group) and anthropological (cultural)

variables that is, sociocultural variables provide further bases for market

segmentation. For example, consumer markets have been successfully subdivided

into segments on the basis of stage in the family life cycle, social class,

core cultural values, subcultural memberships and cross cultural affiliation.

Family Life Cycle

Family life cycle segmentation is based on the premise that

many families pass through similar phases in their formation, growth and final

dissolution. At each phase, the family unit needs different products and

services. Young single people, for example, need basic furniture for their first

apartment, whereas their parents, finally free of child rearing, often

refurnish their homes with more elaborate pieces. Family life cycle is a

composite variable based explicitly on marital and family status but implicitly

refl ects relative age, income and employment status. Each of the stages in the

traditional family life cycle (bachelorhood, honeymooners, parenthood,

post-parenthood and dissolution) represents an important target segment to a

variety of marketers. For example, the financial services industry segments

customers in terms of family life-cycle stages because it has been found that

families’ financial needs tend to shift as they progress through the various

stages of life.

Social Class

Social class (or relative status in the community) can be

used as a base for market segmentation and is usually measured by a weighted

index of several demographic variables, such as education, occupation and

income. The concept of social class implies a hierarchy in which individuals in

the same class generally have the same degree of status, whereas members of

other classes have either higher or lower status. Studies have shown that

consumers in different social classes vary in terms of values, product

preferences and buying habits. Many major banks and investment companies, for

example, offer a variety of different levels of service to people of different

social classes (e.g. private banking services to the upper classes). Some

investment companies appeal to upper-class customers by offering them options

that correspond to their wealthy status. In contrast, a financial programme

targeted to a lower social class might talk instead about savings accounts.

Culture and Subculture

Some marketers have found it useful to segment their markets

on the basis of cultural heritage because members of the same culture tend to

share the same values, beliefs and customs. Marketers who use cultural

segmentation stress specific, widely held cultural values with which they hope

consumers will identify. Cultural segmentation is particularly successful in international

marketing, but it is important for the marketer to understand fully the target

country’s beliefs, values and customs (the cross-cultural context).

Within the larger culture, distinct subgroups (subcultures)

are often united by certain experiences, values or beliefs that make effective

market segments. These groupings could be based on a specific demographic

characteristic (such as race, religion, ethnicity or age) or lifestyle

characteristic (teachers, joggers). Research on subcultural differences, which

will be discussed more fully in next plengdut post , tends to reveal that consumers are

more responsive to promotional messages that they perceive relate to their own

ethnicity.

Culturally distinct segments can be prospects for the same

product but are often targeted more efficiently with different promotional

appeals. For example, a bicycle might be promoted as an efficient means of

transport in Asia and as a health-and-fitness product in Finland. Similarly, a

fishing rod or shotgun could be advertised in many parts of the world as a way

to put food on the dinner table but might be promoted in the UK as leisure-time

sporting equipment.

In a study that divided China’s urban consumers into four

segments (‘working poor’, ‘salary class’, ‘little rich’, and ‘yuppies’), the

researchers found that for all four groups television was the most popular

medium of entertainment and information. However, the working poor spent the

most time listening to radio, while yuppies and the little rich spent the most

time reading newspapers and magazines.

Cross-cultural or Global Marketing Segmentation

As the world has become smaller, a true global marketplace

has developed. For example, as you read this you may be sitting on an IKEA

chair or sofa (Sweden), drinking Earl Grey tea (England), wearing a Swatch

watch (Switzerland), Nike trainers (China), a Polo golf shirt (Mexico) and

Dockers trousers (Dominican Republic). Some global market segments, such as

teenagers, appear to want the same types of products, regardless of which nation

they call home products that are trendy, entertaining and image-oriented. This

global ‘sameness’ allowed Reebok, for example, to launch its Instapump line of

trainers using the same global advertising campaign in approximately 140

countries.

Use-related segmentation

An extremely popular and effective form of segmentation

categorises consumers in terms of product, service or brand usage

characteristics, such as level of usage, level of awareness and degree of brand

loyalty.

Rate of usage segmentation differentiates among heavy users,

medium users, light users and non-users of a specific product, service or

brand. For example, research has consistently indicated that between 25 and 35

per cent of beer drinkers account for more than 70 per cent of all beer

consumed. For this reason, most marketers prefer to target their advertising

campaigns to heavy users rather than spend considerably more money trying to

attract light users. This also explains the successful targeting of light beer

to heavy drinkers on the basis that it is less filling (and, thus, can be

consumed in greater quantities) than regular beer. Recent studies have found

that heavy soup consumers were more socially active, creative, optimistic,

witty and less stubborn than light consumers and non-consumers, and they were

also less likely to read entertainment and sports magazines and more likely to

read family and home magazines. Likewise, heavy users of travel agents in

Singapore were more involved with and more enthusiastic about holiday travel,

more innovative with regard to their selection of holiday travel products, more

likely to travel for pleasure, and more widely exposed to travel information

from the mass media.

Marketers of a host of other products have also found that a

relatively small group of heavy users accounts for a disproportionately large

percentage of product use; targeting these heavy users has become the basis of

their marketing strategies. Other marketers take note of the gaps in market

coverage for light and medium users and profitably target those segments. Table

3-6 presents an overview of a segmentation strategy especially suitable for

marketers seeking to organise their

database of customers into an action-oriented framework. The

framework proposes a way to identify a firm’s best customers by dividing the

database into the following segments:

- L oLows (low current share, low-consumption customers),

- HiLows (high current share, low-consumption customers),

- LowHighs (low current share, high-consumption customers), and

- HiHighs (high current share, high-consumption customers).

Moreover, the framework suggests the following specific

strategies for each of the four segments: ‘starve’ the LoLows , ‘tickle’ the

HiLows , ‘chase’ the LowHighs , and ‘stroke’ the HiHighs.

In addition to segmenting customers in terms of rate of

usage or other usage patterns, consumers can also be segmented in terms of

their awareness status. In particular, the notion of consumer awareness of the

product, interest level in the product, readiness to buy the product or whether

consumers need to be informed about the product are all aspects of awareness.

Sometimes brand loyalty is used as the basis for

segmentation. Marketers often try to identify the characteristics of their

brand-loyal consumers so that they can direct their promotional efforts to

people with similar characteristics in the larger population. Other marketers

target consumers who show no brand loyalty (‘brand switchers’) in the belief

that such people represent greater market potential than consumers who are

loyal to competing brands. Also, almost by definition, consumer innovators –

often a prime target for new products – tend not to be brand loyal. ( plengdut post next discusses the characteristics of consumer innovators.)

Increasingly, marketers stimulate and reward brand loyalty

by offering special benefits to consistent or frequent customers. Such frequent

usage or relationship programmes often take the form of a membership club (e.g.

Hertz Number 1 Club Gold, KLM and Air France’s joint programme ‘Flying Blue’,

or the Hilton HHonors). Relationship programmes tend to provide special

accommodation and services, as well as free extras, to keep these frequent

customers loyal and happy.

TABLE 6 A framework for segmenting a firm’s database of customers

SEGMENT NAME

|

SEGMENT CHARACTERISTIC

|

COMPANY ACTION

|

LoLows

|

Low current share, low-consumption customers

|

Starve

|

HiLows

|

High current share, low-consumption customers

|

Tickle

|

LowHighs

|

Low current share, high-consumption customers

|

Chase

|

HiHighs

|

High current share, high-consumption customers

|

Stroke

|

Source : Adapted from Richard G. Barlow, ‘How to Court

Various Target Markets’, Marketing News, 9 October 2000, 22.

Usage-situation segmentation

Marketers recognise that the occasion or situation often

determines what consumers will purchase or consume. For this reason, marketers

sometimes focus on usage-situation segmentation as a variable. The following

three statements reveal the potential of situation segmentation: ‘Whenever our

daughter Jamie gets a rise or a promotion, we always take her out to dinner’;

‘When I’m away on business for a week or more, I try to stay at a Radisson

hotel’; ‘I always buy my wife flowers on her birthday’. Under other

circumstances, in other situations and on other occasions, the same consumer

might make other choices. Some situational factors that might infl uence a

purchase or consumption choice include whether it is a weekday or weekend (e.g.

going to the cinema); whether there is sufficient time (e.g. use of regular

mail or express mail); whether it is a gift for a girlfriend, a parent or a

self-gift (a reward to one’s self).

Many products are promoted for special usage occasions. The

greetings card industry, for example, stresses special cards for a variety of

occasions that seem to be increasing almost daily (Grandparents’ Day,

Secretaries’ Day, etc.). The fl orist and confectionery industries promote

their products for Valentine’s Day and Mother’s Day, the diamond industry

promotes diamond rings as an engagement symbol, and the wristwatch industry

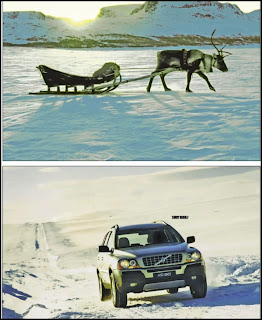

promotes its products as graduation gifts. The Volvo car advertisement in

Figure 1 is based on situational, special usage segmentation. It appeared in

Norwegian newspapers prior to Christmas, covering two consecutive pages. The first

picture portrays Rudolph the Reindeer pulling an empty sleigh, with both Santa

Claus and the Christmas presents obviously missing. The second picture shows a

Volvo XC90 speeding through the snow-covered landscape with someone that might

be Santa Claus sitting behind the wheel. The text, which can’t be

misunderstood, simply says ‘Sorry Rudolf ’.

|

| FIGURE 1 A Volvo occasion-specific advertising campaign telling consumers that Santa Claus has replaced Rudolph the Reindeer with a Volvo XC90 Source : Volvo Personbiler Norge AS/TWBA. |

Benefit segmentation

Marketing and advertising executives constantly attempt to

identify the one most important benefit of their product or service that will

be most meaningful to consumers. Examples of benefits that are commonly used

include financial security, data protection, good health, fresh breath and

peace of mind.

In an article dealing with brand strategies in India, the

point is made that ‘nothing is as effective as segmentation based on the benefits

a group of customers seek from your brand’. To illustrate, the article points

out that in India Dettol soap is targeted at the hygiene conscious consumer –

the individual seeking protection from germs and contamination – rather than

the consumer looking for beauty, fragrance, freshness or economy.

Changing lifestyles also play a major role in determining

the product benefits that are important to consumers and provide marketers with

opportunities for new products and services. For example, the microwave oven

was the perfect solution to the needs of dual-income households, where neither

the husband nor the wife has the time for lengthy meal preparation. Food

marketers offer busy families the benefit of breakfast products that require

only seconds to prepare.

Benefit segmentation can be used to position various brands

within the same product category. The classic case of successful benefit

segmentation is the market for toothpaste, and one article suggested that if

consumers are socially active, they want a toothpaste that can deliver white

teeth and fresh breath; if they smoke, they want a toothpaste to fight stains;

if disease prevention is their major focus, then they want a toothpaste that

will fight germs; and if they have children, they want to lower their dental

bills.

Hybrid segmentation

Marketers commonly segment markets by combining several

segmentation variables rather than relying on a single segmentation base. This

section examines three hybrid segmentation approaches that provide marketers

with richer and more accurately defined consumer segments than can be derived

from using a single segmentation variable. These include psychographic

demographic profiles, geodemographics and VALS.

Psychographic–Demographic Profiles

Psychographic and demographic profiles are highly

complementary approaches that work best when used together. By combining the

knowledge gained from both demographic and psychographic studies, marketers are

provided with powerful information about their target markets.

Demographic psychographic profiling has been widely used in

the development of advertising campaigns to answer three questions: ‘Who should

we target?’; ‘What should we say?’; ‘Where should we say it?’ To help

advertisers answer the third question, many advertising media vehicles sponsor

demographic–psychographic research on which they base very detailed audience

profiles. By offering media buyers such carefully defined dual profiles of

their audiences, mass media publishers and broadcasters make it possible for

advertisers to select media whose audiences most closely resemble their target

markets.

Morever, advertisers are increasingly designing

advertisements that depict in words and/or pictures the essence of a particular

target market lifestyle or segment that marketers want to reach. For example,

Bavac has several advertisements that appeals to specific active and outdoor

lifestyles, and the advertisement presented in Figure 2 is one example.

|

| FIGURE 2 This advertisement targets an active outdoor lifestyle Source : Jagged Globe. |

Geodemographic Segmentation

Specifically, computer software clusters a region or

nation’s neighbourhoods into lifestyle groupings based on postal area codes.

Clusters are created based on consumer lifestyles, and a specific cluster

includes area codes that are composed of people with similar lifestyles widely

scattered throughout the country. Marketers use the cluster data for

direct-mail campaigns, to select retail sites and appropriate merchandise

mixes, to locate banks and restaurants and to design marketing strategies for

specific market segments.

Geodemographic segmentation is most useful when an

advertiser’s or marketer’s best prospects (in terms of consumer personalities,

goals and interests) can be isolated in terms of where they live. However, for

products and services used by a broad cross-section of the public, other segmentation

schemes may be more productive.

Strategic Business Insights VALS™ System

Drawing on Maslow’s need hierarchy and the

concept of social character, in the late 1970s researchers at SRI International

developed a generalised segmentation scheme known as Values and Lifestyles (

VALS™ ). This original system was designed to explain the dynamics of societal

change and was quickly adapted as a marketing tool.

Over the years the VALS™ system (currently owned and

operated by Strategic Business Insights (SBI), a spin-out of SRI International)

was revised to focus more explicitly on explaining consumer purchase behaviour.

The current US VALS™ typology classifies the population into eight distinctive

subgroups (segments) based on consumer responses to 35 attitudinal and four demographic

questions.

|

| Figure 3 depicts the VALS™ classification scheme and offers a brief profile of the consumer traits of each of the VALS™ segments. |

The major

groupings are defined in terms of three primary motivations and a new definition

of resources: the ideals-motivated (consumers whose choices are motivated by

their beliefs rather than by desires for approval), the achievement motivated

(consumers whose choices are guided by the actions, approval and opinions of

others) and the self-expression-motivated (consumers who are motivated by a

desire for social or physical activity, variety and risk-taking). Resources

(from most to least) include the range of psychological, physical, demographic

and material means and capacities consumers have to draw upon, including

education, income, self-confidence, health, eagerness to buy and energy level.

Members of each of the eight VALS™ segments have different

mindsets that drive different consumption patterns – lifestyles,

decision-making styles, communication styles, etc. For instance, Believers are

slow to alter their consumption-related habits, whereas Innovators are drawn to

top-of-the-range and new products, especially innovative technologies.

Therefore, it is not surprising that marketers of intelligent in-vehicle

technologies (e.g. global positioning devices) must first target Innovators,

because they are early adopters of new products.

Komentar

Posting Komentar

Dengan menggunakan kolom komentar atau kotak diskusi berikut maka Anda wajib mentaati semua Peraturan/Rules yang berlaku di situs plengdut.blogspot.com ini. Berkomentarlah secara bijak.